In conversation with actor, director and writer, Chiwetel Ejiofor

By MetFilm School

01 October 2024

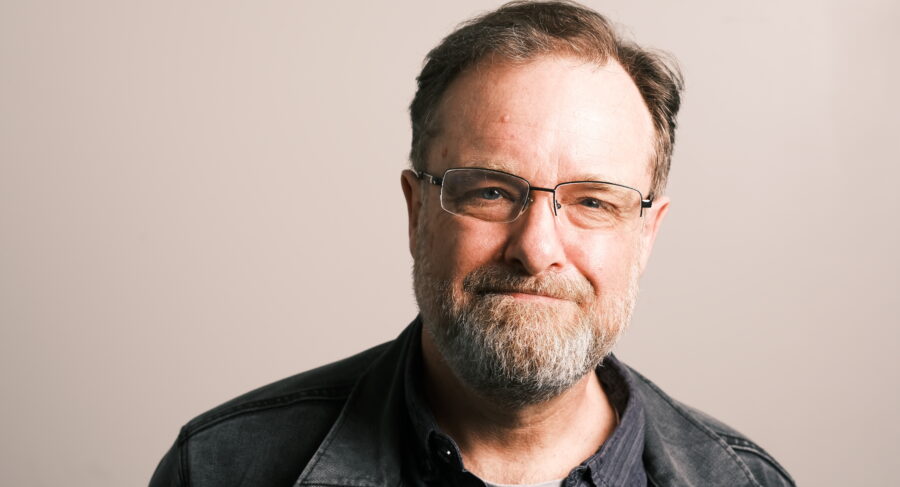

At a recent MetFilm School masterclass, our Manchester students had the exclusive opportunity to engage in a conversation with acclaimed actor, director, and writer, Chiwetel Ejiofor.

A celebrated figure in the film industry for over two decades, Ejiofor has garnered numerous accolades, including a British Academy Film Award and a Laurence Olivier Award, with nominations for an Academy Award, two Primetime Emmy Awards, and five Golden Globe Awards. His impressive body of work includes iconic films such as 12 Years a Slave, Love Actually, Children of Men, The Martian, and The Boy Who Harnessed the Wind.

During the masterclass, Ejiofor delved into his latest project, Rob Peace, which he not only wrote and directed, but also starred in. Based on Jeff Hobbs’ bestselling non-fiction work, the film tells the remarkable story of Robert Peace, a man who grew up in the impoverished streets of Newark and earned a scholarship to Yale. Despite excelling in molecular biophysics and biochemistry, Peace led a double life, selling marijuana to support his father, whom he believed had been unjustly imprisoned.

Ejiofor reflected on the challenges of directing and starring in the film, how he manages to find time for writing, and discussed why representation in film is so important.

Here are just some of the highlights of this incredible session:

Masterclass Highlights

As an actor, did you always plan to move into directing?

Yes, it started quite early in my acting career. I made a film with Stephen Frears and Chris Menges, called Dirty Pretty Things over twenty years ago, now. During that project, I really started to fall in love with the poetry of film, the scope of film, and the emotional resonance that film can occupy. I started to think of it seriously for the first time and began investigating making short films.

How do you balance directing and acting in your films?

Creatively, it’s very exciting to direct and act. As a director, it’s really important to have a real understanding of acting. I think it can be a very good basis for communication with actors, to understand the world and a scene from their point of view.

Working in theatre and on screen for so long has helped me to articulate and communicate clearly as a director. I could play the scene and, in the scene, communicate to the other actors through the way I was playing it. I could communicate a lot of things non-verbally; things about tone, about the direction of the scene, about moments of escalation and moments of quiet or de-escalation. All of these things which would take a lot to talk through in a scene can be communicated through playing the scene – it’s an extra string to the bow.

If you’re acting in a scene as well as directing, it’s a very interesting way of directing. It was much easier, in a way, on my first film (The Boy Who Harnessed the Wind) because it was so isolated out in Malawi, with very few locations. With Rob Peace, it was a much more complicated jigsaw puzzle of a film to make. Consequently, you’re juggling a lot of things in your mind at the same time – it’s a full meal, as a director. You’re acting in it and sort of thinking ‘oh, I’ve got to do this scene, but we also need to be out of this location in 25 minutes!’ – It can be a lot to put on yourself.

What have you learned from directing two feature films that you’re taking on for the future?

You learn an enormous amount from one film to the next, but you don’t necessarily carry all of those things into the next film. You have to reinvent it. You take the information that you know, put it aside and re-engage, understanding that you’re going to have new challenges to face and completely different things you’re going to have to overcome and navigate in your next film. But what you do have is the confidence, I suppose, that you have navigated it before and managed to get through it. You learn how to continue to make films without the same ‘nuts and bolts’ as you may have had on a previous project.

How do you fit writing into your busy schedule?

You have just got to try and write every day. It has to be a constant part of your schedule, and it doesn’t matter what else is going on, you just have to find the time to focus on it. There is a discipline to writing. The battle is just actually doing it. That, and being prepared to accept that it’s not going to be perfect. Whether it’s the first time or the hundredth time you’re sitting at your desk, you are making incremental improvements every time.

I also spend a lot of time reading, and a lot of time subconsciously thinking about characters and the tone and the plot and script, and all these different things, so that when I come back to writing, things are evolving and moving, becoming more complex and interesting – even in those moments where I don’t feel I am doing much. It’s just really important to keep that part of your brain active.

You’re obviously carving out a real passion and identity with developing stories for diverse representations. Would you like to talk about the importance of representation in filmmaking?

I was certainly inspired to make both of my films by the thought that stories like these don’t tend to get a lot of air. It’s a shame, because there are some really interesting and powerful things to say that actually have an impact beyond the stories themselves.

There is this tendency to box everything in and sometimes those boxes make people think that you can just put something in a box and ignore it because it’s not the same box as yours. But, actually, as you uncover the richness of storytelling, you find not only inspiration but also a real connectivity to life, to your own experiences, through the experiences of other people. That is the universality of it.

The Boy Who Harnessed the Wind is a story that exists within the context of a village in Malawi. In that sense, it’s not something that’s typically represented a lot in cinema. However, it covers ideas of generational struggles and complexities in terms of technology and understanding what the future means, what the past means, what family represents, and what the interpersonal dynamics of those families represent at these extreme angles – and how they balance each other – both positive and negative. This is the story of a family going through a famine, so it’s very extreme, but underneath that, it has the same dynamics that we can all relate to and understand, and take lessons from.

I wanted to do a similar thing with Rob Peace. Here you have a family that’s going through incredible highs and devastating lows over a period of two decades. The film focuses on one African American family in an impoverished area of New Jersey, but also comes with this whole question of social mobility. This is what opens up the conversation on what the issues under social mobility are, what the pressure points are. It’s something that affects an enormous amount of people all over the world from all sorts of different backgrounds and all sorts of different communities. I think that we can all recognise that social mobility is something we’ve all had to deal with in some way. Rob’s journey, of course, is an extreme example of that, but it still talks to this idea of social mobility and family, and the pressure points between those two things.

What film have you worked on that left the biggest emotional impact on you and your career?

Working with Steve McQueen on 12 Years a Slave was an extraordinary moment, both in terms of the film winning Best Film at the Academy Awards and the experience of working with Steve. Right from the beginning of that journey, it was like tumbling down the rabbit hole, uncovering all of this emotion and resonance and dynamics and creativity with a beautiful cast. There was a real sense of the unity in storytelling leading to a beautiful film at the end of it.

Earlier in my career, working with pros like Stephen Frears, Spike Lee, Ridley Scott, was so important to my understanding of film and film acting, design and cinematography. These were such rich experiences. I have been very fortunate with the people that I have been able to work with.

And finally, what is your favourite film?

I feel like my favourite film does change and evolve. If I am thinking about film, about how to tell a story, I always go back to Kieslowski’s Dekalog, which is ten hour-long films (so it’s slightly cheating, being ten films!). It’s a very beautiful piece of work centred around the 10 Commandments. It’s set in basically one location and was shot in the 1980s for television. I always look to Dekalog if I am wanting to think about things and get inspired about things like relationship dynamics in film, setting environments, and psychology, and how all that intersects with cinematography. So that’s what I come back to the most.

We’re incredibly grateful to Chiwetel Ejiofor for taking the time to share his valuable insights into directing, writing, and acting with our students. His experiences were truly inspiring, and we can’t wait to see what exciting projects he has in store next!