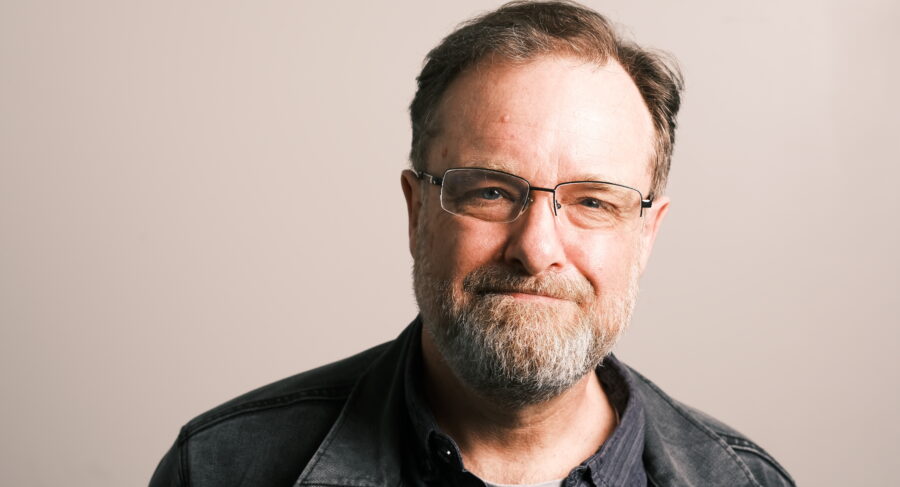

Finn Boylan on Ukrainian Feature Documentary ‘Forsaken Frontier’

By Elise Czyzowska

02 March 2023

Since completing our MA Documentary & Factual degree at MetFilm School Berlin, Finn Boylan has specifically focused on telling stories from within hostile environments. His work has taken him from Kashmir to Karback, West Bank to West Sahara, and for his current project, to Ukraine.

Finn’s time in Ukraine will form his next feature documentary, which will also be the first feature documentary by Finn House Films, of which he is the founder and CEO.

After travelling to Ukraine through 2022, Finn Boylan spoke to us about the experience of shooting documentaries in hostile environments, and how he prepares for such experiences from both a professional and personal perspective.

Please note: this interview contains discussion of war, including the ongoing conflict in Ukraine.

What was the initial inspiration behind this documentary?

I’ve always been fascinated by history, geopolitics, national/religious conflict, and how it all plays out on the world map. Every nation state that exists today in its modern form, with national borders, is a result of conflict – and growing up in Ireland, I was made very aware of this fact.

When I was just a boy, the peace process in Northern Ireland was signed with the Good Friday agreement, and the decades long conflict in the North ended. I still remember seeing the military border infrastructure coming down.

Then, when my graduation from University College Dublin coincided with the Maidan Revolution in Kyiv, I was glued to it – it was like watching the images of nationalist riots in Northern Ireland in the 1970s and 80s. I was viewing it all through my Irish cultural and historical lens, and even then, in the back of my mind, I knew that I needed to be a part of whatever came next, capturing history as it happened.

Can you share a little more about your time in Ukraine, shooting the initial footage?

I arrived in Ukraine on the 12th of March 2022, less than three weeks into the war. While I’ve crossed dozens of borders through Africa and the Middle East, crossing from Poland at Medyka, in freezing conditions, was chaos like no other.

When I finally got to the Ukranian side, the human cost of what was happening was laid bare to see. Hundreds of thousands of people crammed together in a line that stretched kilometres long, carrying all the belongings they could. The suffering on their faces was surreal, and gave me a taste of what I was going to witness in the coming weeks.

Throughout my time in Ukraine, I found it very hard to film – I did not want to make a ‘snuff film’. I wanted to show the horror of what happened, but being as tactful and respectful as possible. These were, of course, human beings, all loved by someone.

In one particular day, I was with a Ukranian press officer in a village called Bilozerka. We were parked outside a local high school, which had served as the headquarters for Russian operations in the area. We were in the building no less than 5 minutes when the first shell came in. As the shells continued coming in, I knew that we were being targeted, and that our exact location was known.

Luckily, all of us made it out alive from this experience. I consider myself very lucky to be alive, and grateful for every moment I have lived from that point on. Every day is a bonus – I should have died that afternoon.

This is an emotional – and quite a difficult – story to tell. How did you prepare yourself, both as a documentarian, but also a person, before starting the project?

I would say that my previous experiences in hostile environments helped to prepare me. My biggest understanding was the importance of keeping calm, and keeping on, no matter how lost the situation may seem. Emotions can cloud your judgement and cost you your life – everything has to be treated like a military mission.

Coming back to the edits, however, was where my emotions at times got the better of me. While in Ukraine, my camera became a way for me to filter my emotions out – but in the edit, I didn’t have this shield. I was forced to relive every second of my footage, over and over again.

I was definitely not prepared for how difficult this editing process would be. My advice to anyone considering doing something similar is to be prepared for the edit, and to recognise that in many ways, it is more of an emotional challenge than the experience itself.

Building from this last question, how has this project pushed you as a filmmaker?

This project has pushed me in more ways than I fully understand yet. It has given me the determination to get to places that many cameras never made it to, and to force me to rely on myself to bring home the story, no matter the conditions.

I have been forced to perform as a one-man band, from filming, story development, sound, and networking or logistics. I have discovered an energy deep inside that I didn’t know was there.

But all of this being said, there also comes a time when the body begins to shut down. For me, it was also about learning when to rest and recover – which I found incredibly difficult to do. There is no break for the Ukrainians, this is their reality. I have the luxury of being able to take a break, they do not. This was a big motivator for why I have returned to the country.

As CEO of your own production company, Finn House Films, how do you manage the two sides of the creative process?

I’ve found balancing the practical and creative elements of documentary making to be a challenge. I’m definitely more suited to field work, as I’m a very instinctive person – planning everything to the letter is not my style, but there does come a time when it is required.

I’m learning through my mistakes and failures. I believe failure is a road to success, so long as you don’t give up. But I also recognise that some failures don’t come with a second chance, so I’m trying to find a better balance between the practical and the creative. The balance I’d like to find is to be practically planning my work, but still allowing myself the creative fluidity to be reactive to the situation in front of me.

Watch the trailer for Forsaken Frontier, and visit the GoFundMe page for the project here

Finally, how did your MA Documentary & Factual degree prepare you for your career?

My time at MetFilm School was a game-changer for me. It was a steep learning curve too – before joining the School, I’d only picked up a camera for the first time twelve months prior.

MetFilm School gave me three things. It gave me the skills I needed to capture my stories in shots, seriously developing my visual storytelling capabilities. It also gave me the skills to edit my stories together – since these things are intrinsically connected.

And finally, it gave me a huge understanding of how difficult it is to actually market and sell your films. I often think back to a comment from one of my tutors, that ‘it’s often easier for filmmakers to make the film than it is to sell it and get people to watch, because of the gatekeepers in your way’.

- You can learn more and donate to Finn Boyland’s current project on his GoFundMe page.

- Finn Boylan studied MA Documentary & Factual at MetFilm School Berlin. This course is also available at MetFilm School Leeds starting September 2023.